2015 marks the ten year anniversary of the first publication of 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style. It's never been a huge bestseller but it has slowly built an international and diverse audience made up of comics fans, designers, readers of experimental literature, and educators.

Teachers in particular have been real champions of the book. I have visited many classrooms to talk about it and I occasionally receive links to projects students have done based on my book. In a recent Twitter conversation a teacher asked me how I use my book when I'm teaching. After the jump I'll share a few ideas.

This will be a bit of a long post so here's a table of contents of what's up ahead:

I. Further variations on my template

II. Make your own template

III. Build an extended project

IV. For non-artists

The photo at the top of the page is from a project by students of the Lycée Pierre Lescot, a trade-oriented high school in Paris (which I point out only to underscore the fact that these activities are by no means only interesting to literature or art students). I visited them in 2009 only to find that they had done a whole series of activities on 99X (that's how I've taken to abbreviating it recently) including an exhibit of variations on my template page. The photo is from a series of Powerpoint photocomics (a new genre?) that told short stories based on a series of elements from my book and stuff the students came up with.

(Note: I credited students where possible but I don't have everyone's names. Happy to update if anyone wants to send info. Also, you can click on all of the images below to enlarge.)

I. To infinity and beyond

I want to share a few more photos of the French students' work because here we find an example of the most straightforward way to use 99X as the basis of a classroom activity: simply have your students make new variations of my "template" comic. It helps to show them my book first, of course, and to have them read my initial inspiration, Raymond Queneau's Exercises in Style or some of the short texts I list at the bottom before asking them to come up with their own approaches to retelling the story. It can help to do this as a class brainstorming exercise which can also serve as an opportunity to further identify different classes of constraints (POV, parodies, graphic approaches, etc.) or to discuss which constraints might be more productive than others (for example: what's more interesting, copying my template page on tracing paper or attempting to redraw it from memory?). It doesn't matter if they're "artists" or not, part of the fun is finding a way to make a visual response (through tracing, collage, copying and pasting, etc.).

A Roy Lichtenstein version (with a bit of Mondrian thrown in for good measure) next to a "robo-optical" version

This "fragmentary" version shows that you can do a lot with just a little bit of drawing ability and some color.

I still hear from teachers doing this kind of activity with their students. For instance, Derek Beaulieu just sent me this new set of variations from his students at the Alberta College of Art + Design. A few excerpts"

a soundtrack version

LOLcats FTW

Spot on Keith Haring version

A very simple twist, throwing kids into the mix, works very well to explain the confusion of the protagonist (and describes my current daily life quite accurately)

II. Make your own template

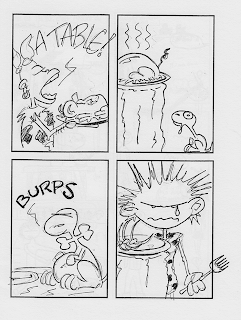

Another approach is to come up with a new template comic or text for your students to riff on. This has the advantage of being easily customizable for different age or skill levels. For example, I did an afternoon workshop with young French kids, between about 8 and 12 years old, at the CIBDI here in Angoulême. I wanted a very simple story for them to work with so I came up with a four panel sequence that wouldn't require a lot of drawing or sophisticated writing:

1. Mom puts food on table, calling child to come eat dinner.

2. A cat climbs up on the table.

3. The cat eats up all the food.

4. The child enters to find the dinner gone, looks disappointed.

We talked about possible approaches you could take and the kids were on their way. Not all of them entirely grasped the concept but even if they just drew a little comic roughly following my script they were having fun and probably learning something. In the end we put together a little minicomic of all the finished (and near-finished) pages. Here are some interesting ones:

This telling of the story is full of anthropomorphism. The cat talks (or "thinks" aloud) and so does the dinner.

A caveman version, why not?

This one is clever: the roles have all been mixed up

III. Build an extended project

If you're working cartooning or art students you can us 99X as the basis for an extended project. You can start with either approach I've laid out above (working from my template or making up a new one) and assign as many variations as you like. (You could also choose a one-page comic they have drawn for a previous assignment as your "template" comic.) You can have students choose their own constraints to work with or you can have them do the same ones, which has the advantage of letting you compare and discuss the results.

In 2013 I spent a week in Viborg, Denmark with the first group of cartooning students they've had at The Animation Workshop. I came up with a 6-panel sequence which we did variations on over the next five days. Here's the script:

1. Student 1 working on comic in classroom.

2. Enter Student 2.

3. S2 sits down next to S1.

4. S1 slides his/her comic to S2.

5. S1 "She's all yours."

6. S1 leaves, S2 starts drawing.

i. template

First I had them draw a "straightforward" version of the story. Of course, right there you start to see that there is no single way to tell the story "straight"—everyone already brings their own tools of drawing style, pacing, framing, and so on:

Here's a relatively straightforward, classic take on the script by Cathrin Peterslund.

.png)

This template by Jacob Thomas Canepa is already imposing its own series of formal choices: repetition, geometric shapes, grayscale...

ii. Genre

The first variation I asked them to do was to retell the story in a genre. Not just any genre though: I talked with each student and we selected genres they had never worked in before—even ones they didn't like. I thought it would be interesting to see how they overcame their dislike and their self-professed ignorance (I knew they would prove themselves wrong, as the results prove):

This war comic by Jam Aden adds a touch of tragedy to the script.

I encourage students to blend more than one genre. Here's a superhero romance comic by Julie Hauge with a healthy dose of comics self-referentiality.

iii. POV/Framing

The next assignment I gave was to play with framing or point of view. I think this might have worked better as the first variation in order to get students focused on the mechanics of storytelling...

Seat's eye view by Bob Lundgreen Kristiansen. Not very glamorous!

The framing on this page by Aske Schmidt Rose focuses tightly on the tip of the pencil, making for an elegant, quasi-abstract comic.

iv. Art forgery

Hommage, parody, counterfeit... I told the students that the goal here was to draw such a convincing copy of an artist's style (not just their drawing style but their way of framing and pacing stories) that we could go sell it on ebay afterwards for a lot of money.

Cathrin Peterslund creates an excellent evocation of Jason's drawing style but note that you can also recognize his characterstic framing, slow pacing, and low-key humor.

If Paul Klee made comics... by Clara Lucie Jetsmark Bjerre.

v. Collaborative extension: 5 obstructions

The last collaboration added the dimension of collaboration to the mix and points to various other directions you could go with this assignment. The logistics of this are worthy of a separate blog post which I will attempt to do sometime (and being a wise blogger I will neither promise anything, nor will I apologize if it takes me three years to do it). For now I'll just say that each student is given the task of coming up with 5 constraints (or "obstructions" to use the terminology proposed by Lars Von Trier, whose playful documentary is the basis of this assignment) that one of their classmates will have to use to make a final variation on their initial "template" pages. The trick to this assignment (as with all constraint-based work, I would argue) is to really encourage the students to come up with tough, even perverse constraints and no softballs. It's not about being mean, of course (and depending on your group you can monitor your students more or less), it's about getting to observe, together, that a-ha! moment when, invariably, every student comes up with an ingenious solution to a tricky constraint.

Three constraints: show only the characters' eyes, use "widescreen" horizontal panels, use only shades of blue — no black.

Just look at Emil Friis Ernst's beautiful solution.The cool blues suggest the glow of the tablet (a lot of these students work digitally) and the horizontal panels adapt easily to the one and then two-eyed framing. The cleverest part to me is the way he uses the reflection in the eyeball and then in the eyeglasses to convey narrative information. (Note two how by giving one character glasses you easily understand that their are two characters in the story despite the tight close-ups.

Now here's a set of constraints that at first glance seems unwieldy if not impossible: characters can't touch the ground? no pants? Silhouettes? Must feature Spiderman??

Yet look at Mathilde Garreau's masterful response. The silhouettes keep the "no pants" rule G-rated while of course Spiderman never touches the ground anyway!

IV. For non-artists

If you don't have time to draw comics or if you are working in a text-only context there's still plenty of stuff you can do with 99X. Recently a group of junior high school students around the city of Poitiers were assigned my book and wrote responses in the form of "exercises in criticism." There was an acronym version, an emoticon version, and even an audio soundscape.

And of course you can always go back to the source and read Raymond Queneau's Exercises in Style in Barbara Wright's translation (an exercise in style of its own). I find it useful to look at a series of even shorter takes on this theme that have been done over the years by various members of Oulipo. This is great because you can find this in English, French, and Spanish at the very least. The English one is by Harry Mathews and it's called "35 Variations on a Theme by Shakespeare" (scroll down to find it among many other gems here); There's a French version by Georges Perec using a line from Proust, and more recently the newest Oulipo member Eduardo Berti made a Spanish version.

I have typically used these texts as a warm up to the comics assignment. I ask my students to come up with ten variations on a saying or famous quote of their choice. I blogged about it and gave examples here.

If you have any questions or additional activities to share I'll hope you'll comment below.

You can purchase the US edition of Matt's book here. There are also UK, French, Spanish, Flemish, Italian (out of print) and Japanese versions available and Matt's always searching for new audiences. In addition, you can find the whole work being serialized online in German and Hungarian.

Read more...